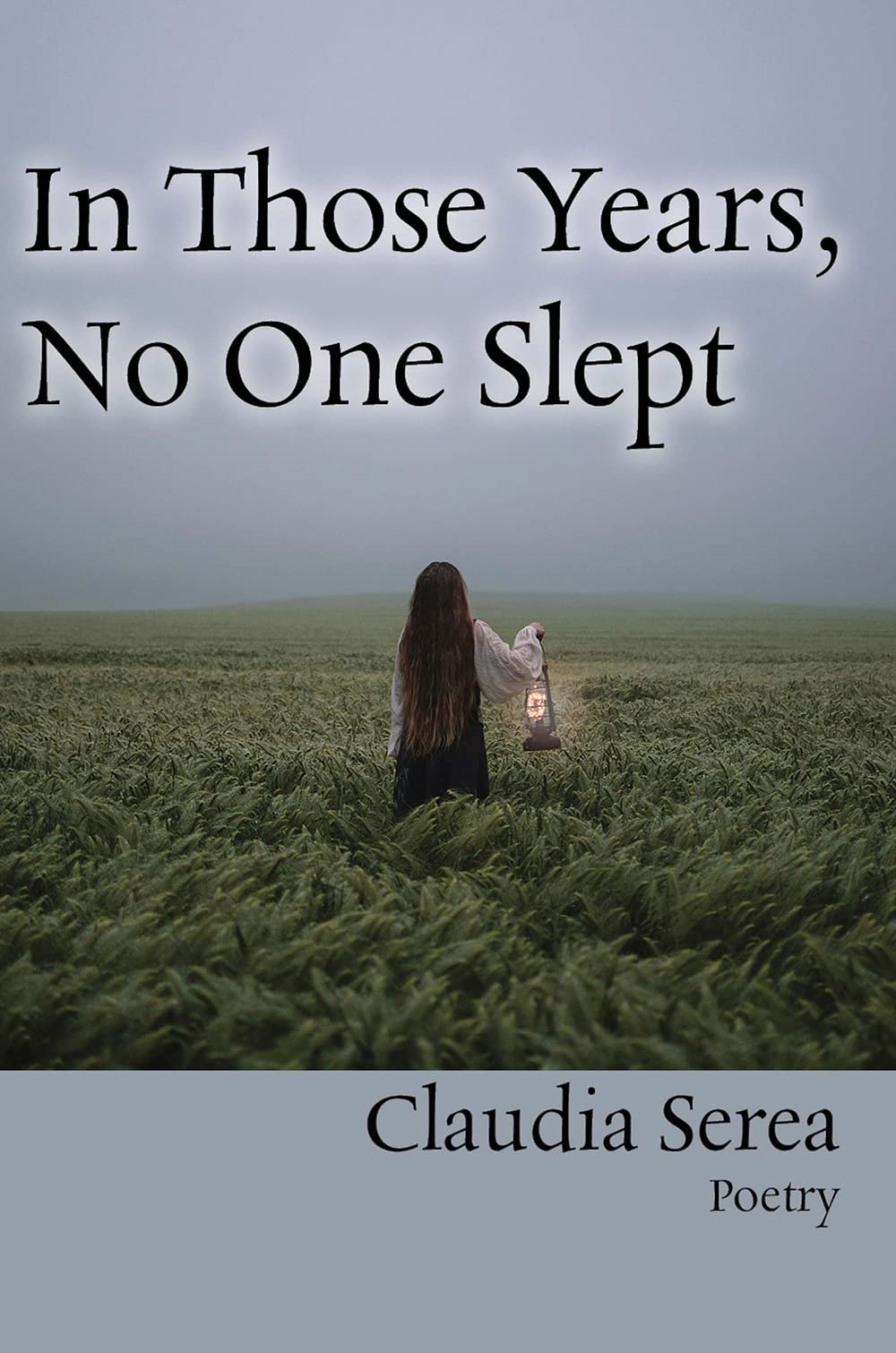

In Those Years, No One Slept

In Those Years, No One Slept by Claudia Serea (Broadstone Books, $27.50)

“He sits in the dark/ and lights matches/ to keep warm.”

In our modern era, a lot of people wonder what the purpose of literature is, perhaps even questioning the relevance of art in general. In a world with so many social problems and so many other ways to stay distracted, why devote time to a poem by Wallace Stevens or a novel by Virginia Woolf? But I think literature is actually the opposite of a distraction, it forces us to confront deeply the social, political, economic, ecological, and moral issues that ensnare our daily lives. And thus while literature itself lacks the ability to solve the vast majority of the issues at hand, it provides a human framework through which to view those issues, thus ensuring that the solutions formulated will perform a greater service to our communities once enacted. In her latest book In Those Years, No One Slept, Claudia Serea once again provides an effective framework through which to view human violence, oppression, and redemption.

What first stood out to me about the book were its dark textures. These pages are filled with decaying human bodies and desolate landscapes. “The eyes of the dead/ bloom chicory and milkweed./ Chewed by rain and lichen,/ the soldier’s cheek crumbles.” The images in these poems often reminded me of woodprint art from the 1930’s with its well-defined but bleak images of human suffering and death. In fact, like a master artist, Serea splashes these pages with vivid colors in a perfectly bound studio. Often these colors are black and red, “the night bleeds its edge into dawn” but her palette also includes some white, “barefoot, I’ll climb/ on a prayer pinned to the moon.”

The reason for the bleakness in these poems is the background. Most of the poems are about life in Serea’s native Romania under a repressive regime. There are themes of tyranny throughout this collection, “my father dug and carried/ wheelbarrows of earth/ in forced labor camps.” This is a land filled with secret police, assassins, and corrupt leaders. Student protests are squashed while tanks and armored vehicles patrol city streets.

As exciting as this political upheaval can be, the most moving poems in the collection are about ordinary lives uprooted. “Some, like my grandfather,/ slept standing,/ hiding among corn stalks/ and listening for dogs.” These desperate accounts of survival reveal the human cost of governmental treachery. Costs so high that some “risked being shot/ for a watermelon rind.” The poet describes these horrific events in an anecdotal way that will grab the attention of even the most cynical reader. The stark reality she presents is the lived experience of the characters, not a bitter polemic.

Maybe this is what provides the palpable sense of isolation in these poems. It made me wonder if this was another effect of tyranny, the removal of the individual from the community. Thus two kids become “two dots/ in the vast, wind-swept plain” and the narrator’s father, upon being released from the Gulag, “walked slowly/ as if still shackled/ startled by dogs/ and any noise.” It seems to be one more brutality of the dictator, to pluck a person from a family, dropping them into a land of terror.

This is not to say that the entire book is long, dark, and hopeless. Amidst the pain, there are warm moments of life spent with family and friends that often include food. “We sit around the simple table/ friends who didn’t get together in years/…we missed the food/ especially the beef and veggies soup.” I am grateful that Serea included these moments in her book, if for no other reason than to show how powerful and resolute the human spirit can be, even amidst the most dire oppression. And as the world rages, this is one of the great purposes of literature, to turn a gaze towards the suffering and to the hope as well.

Benjamin Schmitt

Benjamin Schmitt is the author of four books, most recently The Saints of Capitalism and Soundtrack to a Fleeting Masculinity. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Sojourners, Antioch Review, The Good Men Project, Hobart, Columbia Review, Spillway, and elsewhere. A co-founder of Pacifica Writers’ Workshop, he has also written articles for The Seattle Times and At The Inkwell. He lives in Seattle with his wife and children.