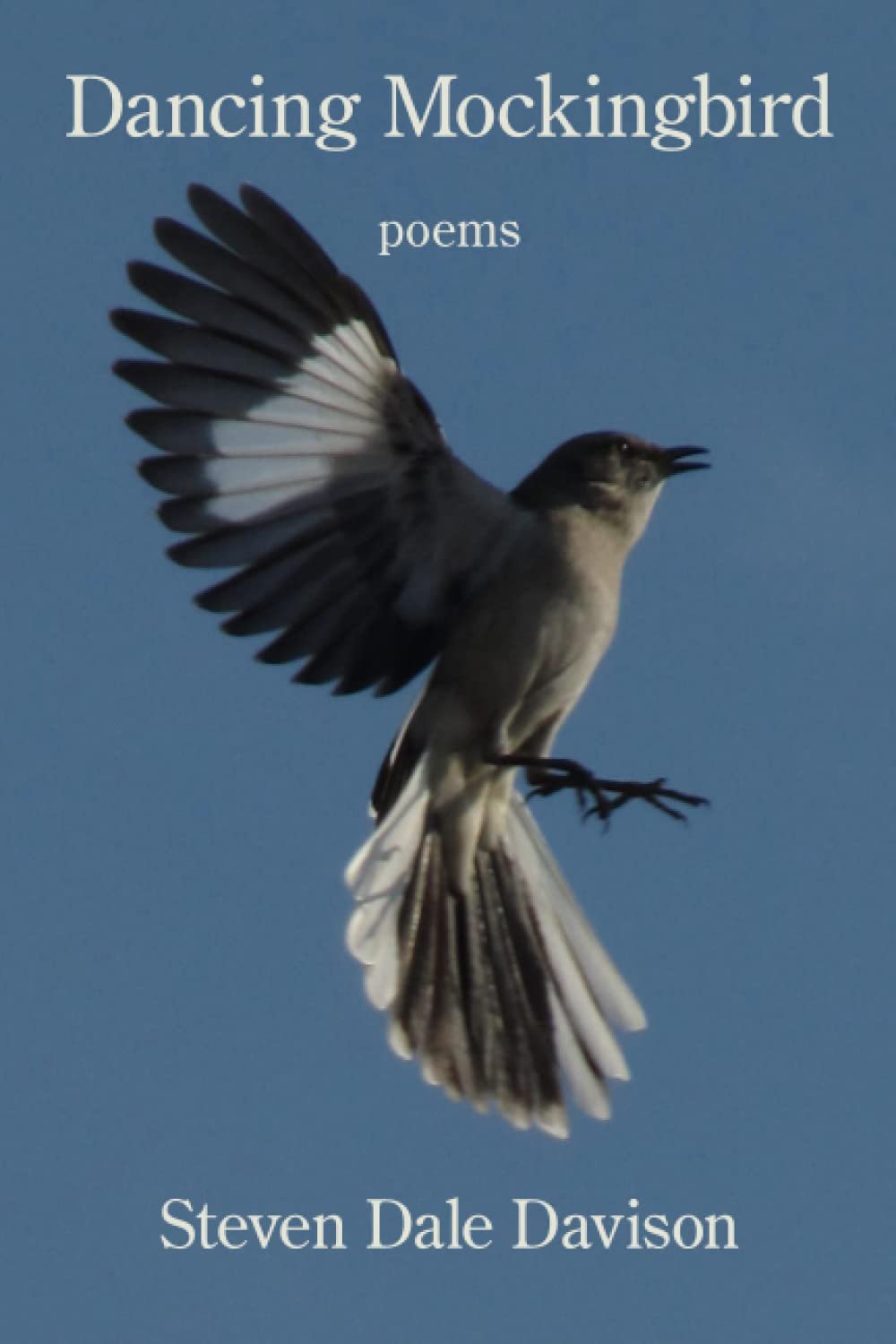

Dancing Mockingbird

Dancing Mockingbird

by Steven Dale Davison, Kelsay Books

Light and distance, height and juxtapose/ of majesty and intimacy, the plush of russet,/ rose, and gold under blue, the off-white rock/ enfolding lakes in the sun’s radiant regard.

Like so many, I spent much of the pandemic indoors. As a rather introverted writer, I must admit that this wasn’t difficult for me. In fact, after a few weeks it became all too easy to remain at home surrounded by the screens of both work and leisure. Eventually I came to miss not only the social connections I had been neglecting, but also my connection to nature. I am fortunate enough to live in a city filled with grand parks and beaches and also surrounded by some of the most majestic terrain in North America, so for the last year I have made a concerted effort to nurture this connection to the natural world. Perhaps this is why I enjoyed so many of the poems in Dancing Mockingbird by Steven Dale Davison, a poet completely immersed in nature.

One of the first things that struck me about the book was the sheer enormity of the landscapes. Lines like, “a storm slides down the mountain to the water,/ whips the waves, then moves on,/ unveiling a westering sun” are truly epic in scale. In this way, Davison reveals himself to be an American poet in the vein of Walt Whitman, whom he acknowledges in this collection. Like Whitman, the continent opens itself up to his pen, "bayous, cut-off oxbows seeping and breeding frogs...the great rivers of the country pay their tribute,/ and ask only passage to the sea.” There is a certain feeling one gets upon looking out from a great vista and Davison captures it well.

From such heights, the poet perceives the unity and wholeness of all nature. The moon, a bird, a mountain, a human watching; for Davison all are unified. There is a certain spirituality to lines like, “earth spins her outsweep tilt to winter/ on v’s of geese. The eyelids of maples/ flutter on the edge of sleep.” This is not dogmatic religious instruction but rather a heightened awareness of our place in the universe. As a reader, I couldn’t help but come away with both a greater sense of purpose and a grave sense of humility.

One of the most important elements in a book of poems is the author’s voice. Is the poet able to write in a way that is unique and interesting enough to hold one’s attention for a book-length work? Davison possesses a fun and original voice that kept me frequently engaged while reading Dancing Mockingbird. “Night does not fall—it glides/ in incremental frequencies/ across the turning earth,” he writes. Later, he shares more insights, “sand holds the laws of its movement/ in the hands of others…leisurely geometries/ pace from crest to crest.” He also uses rhyme, alliteration, and other poetic tools to bring his natural settings to life. There were a few poems in which this voice retreated that didn’t quite work for me. But the poet was at his best when he let his passion for the grandiosity of our universe overwhelm him.

It is the simple scenes that reveal our larger connection to the natural world that make Dancing Mockingbird a worthwhile read. “Suddenly, a windless stillness fell,/ and, almost close enough to touch,/ a herd of white-tailed deer appeared.” These lines reminded me of a week spent in the Sawtooth National Forest near Stanley, Idaho about twenty years ago. On two separate occasions that week I too encountered deer close enough to touch. At the time, it felt downright miraculous. These are the miracles and wonders of the natural world that Davison implores us to explore in Dancing Mockingbird. I intend to heed his call.

Benjamin Schmitt

Benjamin Schmitt is the author of four books, most recently The Saints of Capitalism and Soundtrack to a Fleeting Masculinity. His poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Sojourners, Antioch Review, The Good Men Project, Hobart, Columbia Review, Spillway, and elsewhere. A co-founder of Pacifica Writers’ Workshop, he has also written articles for The Seattle Times and At The Inkwell. He lives in Seattle with his wife and children.