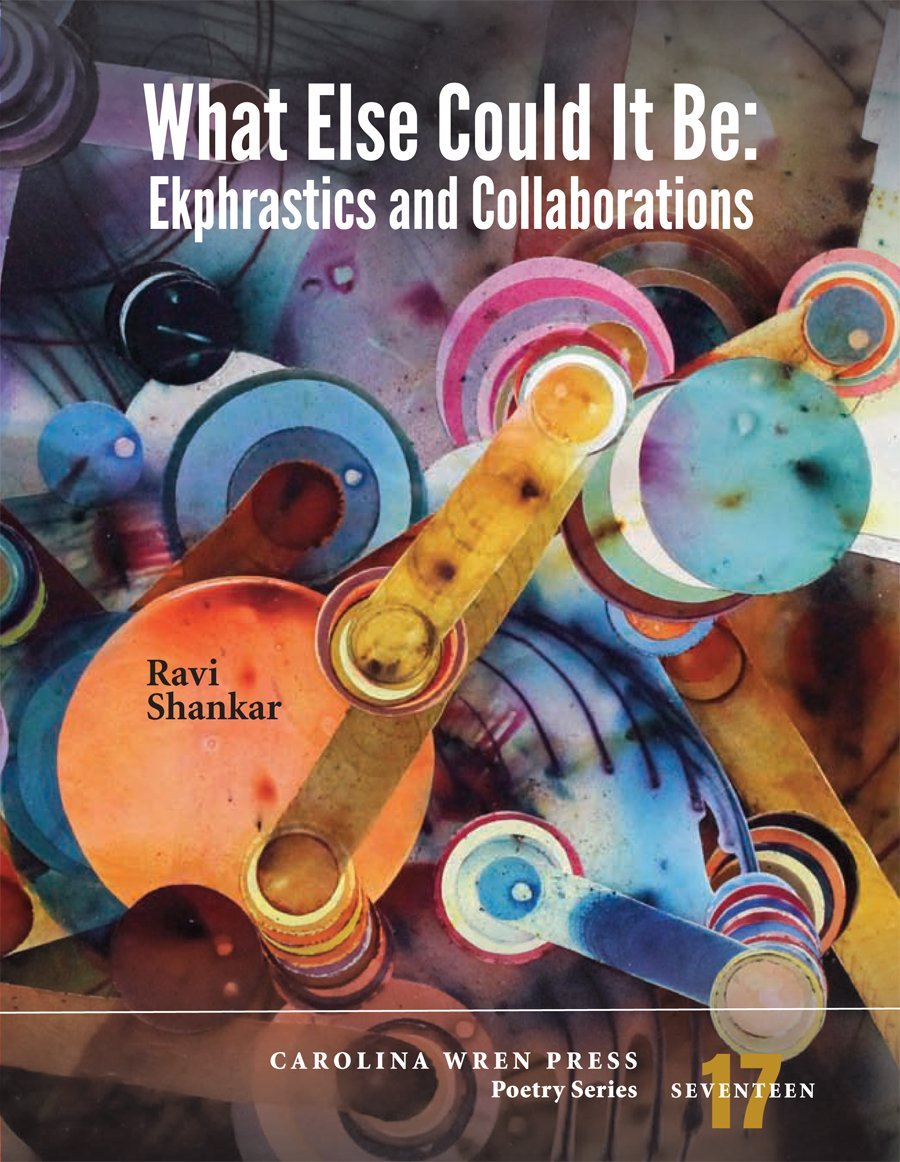

What Else Could It Be: Ekphrastics and Collaborations

What Else Could It Be: Ekphrastics and Collaborations

by Ravi Shankar, Carolina Wren Press, $18.95

Ravi Shankar is a great poet, a scholar, and, over the years, became an editor to reckon with, at the literary magazine he founded, Drunken Boat. His poems are luminous and voluminous; they shimmer with ideas and color and a great love and curiosity for life, art and music. He is widely respected for his advocacy for the poets and people of Singapore; he is a prophet of the polyglot, perhaps diversity’s best muse.

Seeking out voices from all points to include in Drunken Boat, he has looked to the most far flung corners of humanity. Those disparate and multi-cultural themes, voices and places are also reflected in his own work, six books of poems to date, two heady and glorious translations and two incredible anthologies; Norton’s Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry from Asia, the Middle East & Beyond and, most recently, the 2015 Union: 15 Years of Drunken Boat and 50 Years of Writing from Singapore, which he co-edited with Singapore artist, Alvin Pang, published by Ethos books of Singapore. These, along with Carolina Wren Press’ 2015 release What Else Could It Be; Ekphrastics and Collaborations and the 2015 Zubaan press (New Delhi) release of Andal: The Autobiography of a Goddess, translations of the work of the 9th century Indian mystic poet Andal, represent what by anyone’s standards is a prolific writing life.

His most recent book of poems, and the seventeenth in the Carolina Wren Press series, What Else Could It Be: Ekphrastics and Collaborations, is separated into three numbered sections. The first is introduced with a quote from Miles Davis, the second with a quote from Serbian performance artist Marina Abramovic, and the third with a quote by Nietzsche. The first section embraces experiences of music, ancestry, love of nature, and things that have opposites (as in the poem Ephemerality = Permanence); the second section seems engaged with ekphrastic work and has poems introduced by epigraphs by such artists as Miro, Degas, and the sculptor Rosemarie Fiore (I had never heard of her and merely opening her web page filled me with curiosity about her work), and, in the third section, Shankar grapples with the topics of architecture and philosophy. Each section has a flavor of its own and the poems seem to waltz with one another playfully, nodding in tune to the same leitmotifs.

The poems in all three sections hum with intelligent energy and heart, an interesting mix. Because I love the Clash, I was drawn to the poem Sounds like Trax, in the first section, in which Shankar talks of dancing in “that club with pinwheel lights/by the highway off ramp in DC, an outdoor/strip of beach with towering potted plants” and “new punk/rock girls near as the shimmy lasso of a hip” and “bass massive in the ears,” as “the oldest human ritual imagined.”

Shankar has a long poem in the second section entitled Wanton Textiles, in which he talks about finding a home in an artist’s materials: “Yes, Lycra can improve your performance/so let’s stretch together and recover/that original shape our creases keep/ singing about.” The poem travels through materials and sculpture to a trope of oceans and ships and finally links to the classics with a reference to Odysseus and Penelope. It is an epic poem worth spending time with, with many twists of meaning and a sexual denoument: “It is what begins around the waist, the round/and dip, the innie and the outie, the fabric we rue/ that rouses us most.”

It is hard not to read events of poet’s lives into their work, and I often grapple with this. Even the most rudimentary research reveals Shankar’s private life hit some bumpy patches in recent years, and in such poems as Over the Counter, in the third section, you feel the pain of this: “Some kinds of pain/annihilate everything/save origin and throb/crowding the wound/ Other kinds of pain/cannot be indexed/on a 1-10 scale/but are more granular/a keening that takes over/so steadily it resembles/waking and walking,” and “there is no placebo/or panacea, no formulary/pills precisely synthesized/for treatment or cure–/even the tongue/can be bitten.

Researching a bit about Shankar’s life and work, I came upon an essay the poet, who shares a name with an esteemed Indian sitar player, penned for the New Yorker some years back. In it he talks about this name sharing as a “peccadillo of fate”:

“If I had a rupee for every time someone I’ve met has made a Woodstock joke, strummed an air-sitar while twanging nasally, or asked me to arrange a date with my daughter, Norah Jones, I’d be a rich man. Hardly a day passes without my being reminded of the icon of world music who owns my name. I have lived my life as a doppelganger, a secondary Ravi Shankar.

“My identity crisis goes back to kindergarten in suburban Virginia, where my ponytail-wearing, beatifically smiling teacher, Mr. Fatuma, took me aside one day to praise my precocious reading and inform me that I had a special gift — just like the man I was named for! But not until ninth grade did my namesake actually impinge on my world. One day while loitering with my pals, a mini ghetto-blaster pumping out the Stones’ “Paint It Black,” I ventured that I liked that guitar lick.

“‘That’s not a gee-tar, that’s a see-tar,’ a friend mocked. ‘It’s Indian, man. It’s Ravi Shankar. You know — the real one.’”

It was odd to read that essay because for me, Shankar the poet is “the real one” – and I found myself wondering as I spent a month reading his work in this new book and his essay in Union and translations of andal, and considering his larger life’s circumstances and the abject beauty of his words, if he knew that people feel that way. I have a suspicion that many, many do.

Elizabeth Cohen teaches creative writing at SUNY Plattsburgh and through Gotham Writer’s Workshops in New York. She is the author of The Hypothetical Girl, a collection of short stories, The Family on Beartown Road and four books of poetry, including What the Trees Said. She lives in upstate New York with her daughter, Ava, and way too many cats.