A Brother’s Testimony

A Brother’s Testimony

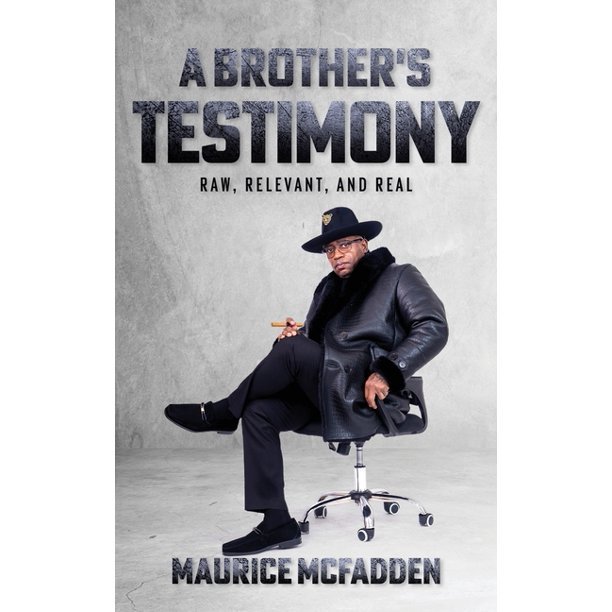

By Maurice McFadden, Mynd Matters Publishing, $14.99

In his book, New Seeds of Contemplation, Thomas Merton, a former trappiest monk from the Abbey of Gethsemani, wrote that a poet “should be an apostle by being first of all a poet, not try to be a poet by being first of all an apostle. For if he presents himself to people as a poet, he is going to be judged as a poet and if he is not a good one his apostolate will be ridiculed.”

In his new book of poetry, A Brother’s Testimony, Maurice McFadden has proven to be a good poet and, most importantly, a good apostle. The book cover rightly acknowledges that McFadden’s language is “Raw, Relevant and Real.” A similar voice to the Book of Psalms, this hard-edged poetry collection explores the journey of a man searching for God in times of trials, tribulations, and seemingly unconquerable hardships.

Originally from the Bronx, New York, McFadden grew up in a world of violence and penury. “I am a prisoner in my own house,” he writes, “Gunfire outside my window goes pop, pop,” and “Pains of hunger heard each day/Children sit in poverty and slowly fade away.” But McFadden successfully escaped from this life, at least temporarily. He worked in the entertainment industry, served in the US Army, and was a Northern California Amateur Boxing Champion. But regardless of his stable career decisions and material success, he was an alcoholic. His drinking eventually returned him to a life he grew up in. In the title poem, “A Brother’s Testimony,” he writes, “I drank to black out most days/What kind of man was I to rationalize the truth about my drink?/It had ruined much in my life.”

Alcohol can lead to poor decisions. In the prose poem, “Monterey, California,” McFadden shares an experience that was “one of the/worst weekends of my life.” He and his friends, after a night of drinking, pulled into a McDonalds. Five ill-behaved white guys pulled in around the same time. “We heard them call us niggers,” McFadden writes. Instead of ignoring them and leaving the scene, McFadden and a friend of his yelled, “Fuck you, crackers.” Verbal outburst turned physical. The police showed up and McFadden and his friends were arrested. Evidently, the white guys were released without being charged. The long and short of it, McFadden spent some time in jail and the Army subsequently “offered me a general discharge under/honorable conditions.”

It seems to me that McFadden and his friends, influenced by alcohol, pridefully engaged with five racist morons and probably should have just ignored them, bought their food, and peacefully left the McDonald’s parking lot. He even admits making such a mistake in the poem, “The Sin of Pride,” when he writes, “Pride is destroying me/Pride is taking my glory.” However, a part of me feels good that a bunch of white privileged turd burglars got the shit kicked out of them and, to some degree, McFadden feels good about it as well. But the main point of the poem, I think, is the unjustifiable racial profiling conducted by the police. If the police found just cause to arrest McFadden and his friends, then they should have found a good reason to arrest the five white guys as well.

But regardless of this unfortunate and unnecessary racially motivated encounter, America has come a long way. Racism is not like it was in, let’s say, 19th century America. Gone are the days of racial slavery, the Black Codes, and Jim Crow. But do not misunderstand me. Racism is still a big problem.

On average, black drivers get pulled over by the police more than their white peers. McFadden can attest to this statistic. In the poem “Sorry For Your Ignorance,” he writes, “Did my car you cannot afford draw you to me/Or was it my baseball cap and my hoodie/I wore to protect me from the rain/In pursuit/So, for three miles you must follow me?” And then, the crushing line, “Does not matter what you might think but all Black men/do not look alike.”

McFadden implies that his alcohol addiction was the root of most of his problems and does not always blame racists or law enforcement officers that racially profile suspects. His excessive drinking not only ruined much of his life, but it ruined the lives of many people around him, particularly his family. In the poem,” Locked Up,” he writes, “I was sleeping off a hangover from the night before at my mother’s house.” The police arrived and informed him that his wife “was pressing assault charges against me, and I had/to come with them.” McFadden “avoided jail time but had/an order of protection against me and had to report to the/City of New York Department of Probation for a year.” Fifteen years of marriage and it was over in an instant. Years later, he finally took ownership “for what I had did to her and the kids.”

With his many hardships and obstacles, especially his battle with addiction, McFadden never gave up hope that he would one day pull himself out of violence and poverty once again. But in order to do this, he realized he needed God’s help. In the poem, “Shifts Happen,” McFadden writes, “God’s shift changes our destination.” And again, in the poem, “Write The Vision,” McFadden writes, “Strengthen my faith in you/Knowing there is a divine plan that I may not always understand.” And finally, in the poem, “Go After It,” McFadden states, “But it is all in God’s timing.”

I thank Maurice McFadden for writing this courageous book. He suffered many, often unjustifiable trials, tribulations, and hardships, but ultimately came out on top. He conquered the struggles in his life because he realized, unlike many people in his position, that he needed God’s grace and guidance to do so.

In the poem, “Grace,” McFadden writes, “But grace was the best thing for me/Because you save me Lord.” A good lesson for all of us. So those of us that might be suffering hardship and times of trial, “Give your dreams a chance,” McFadden encourages us. “If I can do it, so can you.”

Matthew A. Hamilton

Matthew A. Hamilton holds an MFA from Fairfield University and a MSLIS from St. John’s University. Currently, he is a graduate student at the University of Alabama. His research focus is blockchain technology and how it can contribute to improve transparency and accountability in government. His stories and poems have appeared in a variety of national and international journals. His chapbook, The Land of the Four Rivers, published by Cervena Barva Press, won the 2013 Best Poetry Book from Peace Corps Writers. His second poetry collection, Lips Open and Divine, was published in 2016 by Winter Goose. The Wishing Tree, a novel about the 1915 Armenian Genocide, was published by Winter Goose in 2020. He and his wife live in Richmond, Virginia. Visit him here.